05 Feb 2026

Because there is currently no .NET (dotnet) example on how to use the Google Vertex AI Agent Engine agent in a project, I decided to write one as there are misleading parts without any documentation.

First things first

You will need to install the NuGet package Google.Cloud.AIPlatform.V1 and Google.Apis.Auth for the authentication part.

To check whether there are any issues with the dotnet libraries, you can visit the official GitHub repository.

Authentication

For authentication, you can choose to authenticate the machine running the service, but in my case, it was easier to just export the service account credentials from Google as a JSON file. I used the documentation from here to get the JSON.

Google recently updated its credential creation process, so GoogleCredential.FromJson() method is deprecated, and a new way must be used with CredentialFactory.

var credentialsPath = "service-account-credentials.json";

var googleCredential =

CredentialFactory.FromFile<ServiceAccountCredential>(mappedPath).ToGoogleCredential();

Vertex AI Reasoning Engine Client

To be able to use the AI Agent, you will first need to create a ReasoningEngineExecutionServiceClient that can then be called for different operations. For this, use the ReasoningEngineExecutionServiceClientBuilder class, specifying the endpoint and using the credentials from the previous step.

Endpoint example: us-central1-aiplatform.googleapis.com, the us-central1 is where the Vertex AI models are also deployed.

var clientBuilder = new ReasoningEngineExecutionServiceClientBuilder

{

Endpoint = _endpoint,

GoogleCredential = googleCredential

};

_client = clientBuilder.Build();

I usually put the auth and the client in the constructor of the class I will use.

Calling the Agent

The Reasoning Engine client provides two (three if we consider the async too) methods that can be called to interact with the agent QueryReasoningEngine and StreamQueryReasoningEngineRequest.

The misleading QueryReasoningEngine

Nothing in the documentation suggests that QueryReasoningEngine cannot be used to query the agent. The class is really misleading.

When querying the agent’s operation schema, you even get back 2 operations (stream_query and async_stream_query) that, in theory, would be called from QueryReasoningEngine.

...

{

"description": "Deprecated. Use async_stream_query instead.\n\n Streams responses from the ADK application in response to a message.\n\n Args:\n message (Union[str, Dict[str, Any]]):\n Required. The message to stream responses for.\n user_id (str):\n Required. The ID of the user.\n session_id (str):\n Optional. The ID of the session. If not provided, a new\n session will be created for the user.\n run_config (Optional[Dict[str, Any]]):\n Optional. The run config to use for the query. If you want to\n \r\n pass in a `run_config` pydantic object, you can pass in a dict\n representing it as `run_config.model_dump(mode=\"json\")`.\n **kwargs (dict[str, Any]):\n Optional. Additional keyword arguments to pass to the\n runner.\n\n Yields:\n The output of querying the ADK application.\n ",

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"message": {

"anyOf": [

{

"type": "string"

},

{

"additionalProperties": true,

"type": "object"

}

]

},

"user_id": {

"type": "string"

},

"session_id": {

"type": "string",

"nullable": true

},

"run_config": {

"type": "object",

"nullable": true

}

},

"required": [

"message",

"user_id"

]

},

"api_mode": "stream",

"name": "stream_query"

},

{

"description": "Streams responses asynchronously from the ADK application.\n\n Args:\n message (str):\n Required. The message to stream responses for.\n user_id (str):\n Required. The ID of the user.\n session_id (str):\n Optional. The ID of the session. If not provided, a new\n \r\n session will be created for the user.\n run_config (Optional[Dict[str, Any]]):\n Optional. The run config to use for the query. If you want to\n pass in a `run_config` pydantic object, you can pass in a dict\n representing it as `run_config.model_dump(mode=\"json\")`.\n **kwargs (dict[str, Any]):\n Optional. Additional keyword arguments to pass to the\n runner.\n\n Yields:\n Event dictionaries asynchronously.\n ",

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"message": {

"anyOf": [

{

"type": "string"

},

{

"additionalProperties": true,

"type": "object"

}

]

},

"user_id": {

"type": "string"

},

"session_id": {

"type": "string",

"nullable": true

},

"run_config": {

"type": "object",

"nullable": true

}

},

"required": [

"message",

"user_id"

]

},

"api_mode": "async_stream",

"name": "async_stream_query"

},

{

"description": "Streams responses asynchronously from the ADK application.\n\n In general, you should use `async_stream_query` instead, as it has a\n more structured API and works with the respective ADK services that\n you have defined for the AdkApp. This method is primarily meant for\n invocation from AgentSpace.\n\n Args:\n request_json (str):\n Required. The request to stream responses for.\n ",

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"request_json": {

"type": "string"

}

},

"required": [

"request_json"

]

},

"api_mode": "async_stream",

"name": "streaming_agent_run_with_events"

}

...

But when you call it that way, you get an error that the operation is not found, and it enumerates the available operations.

{"detail":"Agent Engine Error: Default method `async_stream_query` not found. Available methods are: ['get_session', 'async_create_session', 'async_add_session_to_memory', 'async_get_session', 'async_delete_session', 'list_sessions', 'delete_session', 'async_list_sessions', 'async_search_memory', 'create_session']."}")

Using StreamQueryReasoningEngineRequest

So the correct way to call the agent with a prompt and get a response is via StreamQueryReasoningEngine.

var query = "...";

var input = new Struct();

input.Fields.Add("user_id", Value.ForString("test_user"));

input.Fields.Add("message", Value.ForString(query));

input.Fields.Add("session_id", Value.ForString("12345")); // Optional; only interesting when adding follow up to the conversation.

var stream = _client.StreamQueryReasoningEngine(new StreamQueryReasoningEngineRequest

{

ReasoningEngineName = ReasoningEngineName.Parse(AgentName),

Input = input,

});

var finalResponse = "";

await foreach (var response in stream.GetResponseStream())

{

var chunk = response.Data.ToStringUtf8();

// Deserialize the JSON response into the StreamQueryReasoningEngineResponse model

var agentResponse = JsonSerializer.Deserialize<StreamQueryReasoningEngineResponse>(chunk);

// Extract the text content from the response

if (agentResponse?.Content?.Parts is { Count: > 0 })

{

var text = agentResponse.Content.Parts[0].Text;

finalResponse += text;

}

}

return finalResponse;

}

AgentName example: projects/{project-id}/locations/{location}/reasoningEngines/{agent-id} that in the end should look similar to this projects/123456789012/locations/us-central1/reasoningEngines/1234567890123456789

Note: The class StreamQueryReasoningEngineResponse that is used for deserialization is a custom one I created based on the response. You can ask the AI to generate it based on the response. The response may differ based on the tools/model/agent you use.

04 Feb 2026

In the project I am currently working on, we inherited a codebase written in an older version of .NET Framework. The ASP.NET part of it was still using synchronous controller methods. This wasn’t changed for a long time because, why bother if it works? Then, some newer methods became async Task type methods with async code. Then we continued to have both, with some wiring when we went from sync to async. Then a performance problem came up. The issue was weird, and we didn’t know whether the wiring was at fault or not. So we just went in and updated all the old methods into async methods without changing the logic or anything.

To our surprise, the same code, on the same .NET Framework, on the same machine, started responding 29% better. Then we did some minor fixes, and that percent became even higher to ~44%

| Iteration |

From (ms) |

To (ms) |

Absolute Improvement (ms) |

Improvement (%) |

| Sync → Async controllers |

276 |

197 |

79 |

28.6% |

| Sync → Async controllers + code optimizations |

276 |

155 |

121 |

43.8% |

These results caught me off guard, so I wanted to find out what was happening behind the scenes, how async-await actually works, and why it led to such a big performance boost.

What is asynchronous programming?

First, let’s look at a few definitions of asynchronous programming:

[!NOTE] JavaScript

Asynchronous programming is a technique that enables your program to start a potentially long-running task and still be responsive to other events while that task runs, rather than having to wait until that task has finished. Once that task has finished, your program is presented with the result.[^1](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Learn_web_development/Extensions/Async_JS/Introducing)

[!NOTE] Rust

Asynchronous programming is an abstraction that lets us express our code in terms of potential pausing points and eventual results that take care of the details of coordination for us. [^2](https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch17-00-async-await.html)

[!NOTE] Dotnet

Async methods are intended to be non-blocking operations. An await expression in an async method doesn’t block the current thread while the awaited task is running. Instead, the expression signs up the rest of the method as a continuation and returns control to the caller of the async method.[^3](https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/dotnet/csharp/asynchronous-programming/task-asynchronous-programming-model#threads)

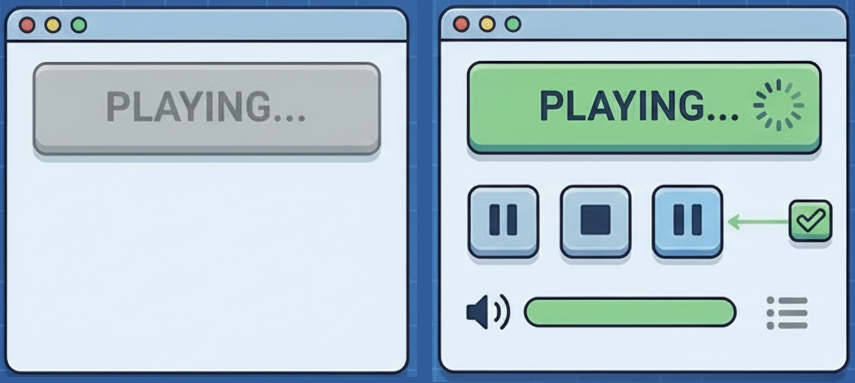

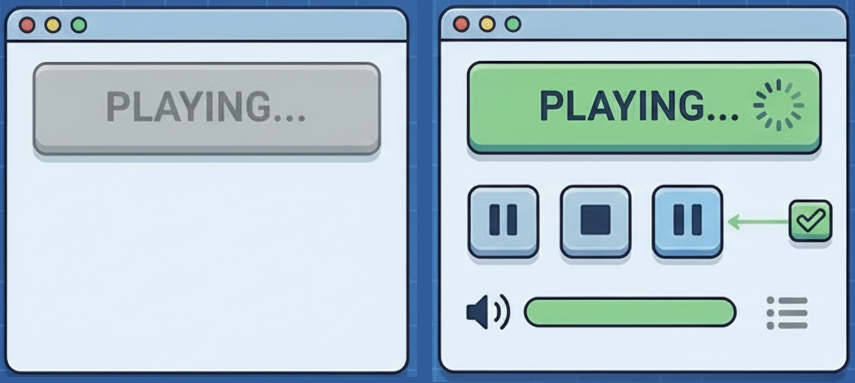

What we want to achieve with async code is not to block other operations from executing while a longer-running task is being processed. This provides a pleasant user experience. Think of a button that plays a song: once pressed, nothing else can happen; you cannot pause it, stop it, change the volume, or manage the playlist until the song finishes. This is what async enables.

Similar solutions include using events or callbacks. Events enable operations to be performed at command when the event is triggered. Callbacks are another way to pass an operation to another operation, with the expectation that the second will call the first when needed. Both are used in different scenarios, but without oversight, they can be hard to follow and lead to event spaghetti, callback hell, or other popular code disasters.

The async-await combo became popular because of this. It enables writing code that looks like normal synchronous code while adding asynchronous capabilities in a simple way.

It’s important to clear up two related concepts that people often mix up: concurrency and parallelism. Knowing the difference helps you get the most out of async programming.

Concurrency ≠ Parallelism: understanding the difference

Both seem to do multiple things at once, and they do; the difference is in how they do it.

To better understand it, we need to realize that these notions apply to the CPU. Meaning that the operating system has other system components that also do work, and when we are talking about concurrency, we mainly are thinking about what the CPU can do while the other components respond. We can group these system components and name them I/O-bound tasks, such as waiting for the disk to read a file’s contents, waiting for a network response, or waiting for results from a database. Even with a single-core CPU, we can better utilize it while we wait for I/O (Input/Output) responses and handle the next task.

The example would be having one chef making a pasta dish. First, a pot is put on the stove filled with water. Then some salt is added to the pot, and the heat is turned on. While we wait for the pasta water to boil, we can do the next task, like grate some cheese. When the water reaches a boil, we return and put the pasta in, then do another task while it cooks, and so on.

For parallelism, we need multicore processors, which have been a feature since 2005. Meaning that if you run something on a modern PC, it will most likely be on a multicore processor (CPU). Usually, a thread pool manages tasks and the available threads to perform the work.

If we were to go on the previous example. This would mean that multiple chefs are making a pasta dish. Chef-1 could take care of the pasta task, and Chef-2 could do the sauce for it.

If you observe closely, you can see that in this example, the chefs work in parallel but not concurrently. Each chef handles the entire task, start to finish, by themselves, making each task “synchronous”.

Mixing the two concepts, concurrency and parallelism, would mean having Chef-1 put the water to boil while, in parallel, Chef-2 cuts onions for the sauce. If Chef-1 finishes faster, it could continue chopping tomatoes for the sauce. Then, when Chef-2 finishes, it can continue the pasta task or finish it if Chef-1 is still busy.

This is what async-await actually does behind the scenes. It helps with doing tasks so that blocked parts can be resumed later. If the context allows another thread to pick up the task, it can happen, but it is not guaranteed. This is why concurrency does not always guarantee parallelism. All other threads can be busy with other things, so the same thread will be used when the I/O operation finishes.

In summary, embracing asynchronous programming with async-await in .NET is more than a modern trend. It’s a practical way to achieve real-world performance improvements, often with minimal code changes. By clarifying the concepts of concurrency and parallelism and understanding their impact, we can write applications that are not only faster but also more responsive and maintainable. Revisiting and updating legacy codebases can yield surprising benefits and remind us that sometimes, questioning “what just works” leads to breakthroughs that benefit both developers and users alike.

12 Dec 2025

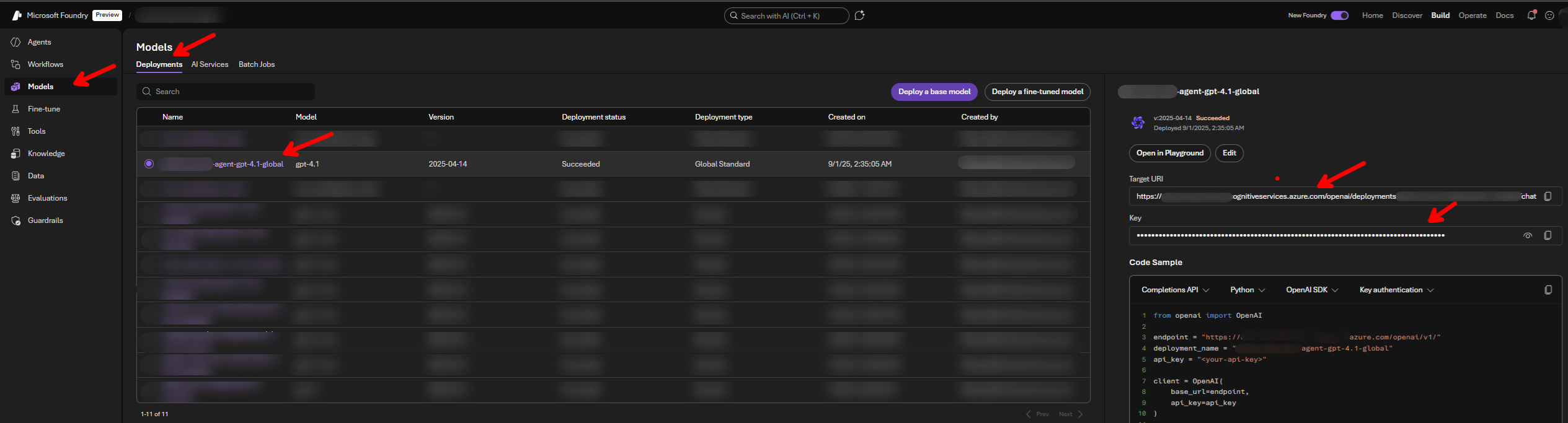

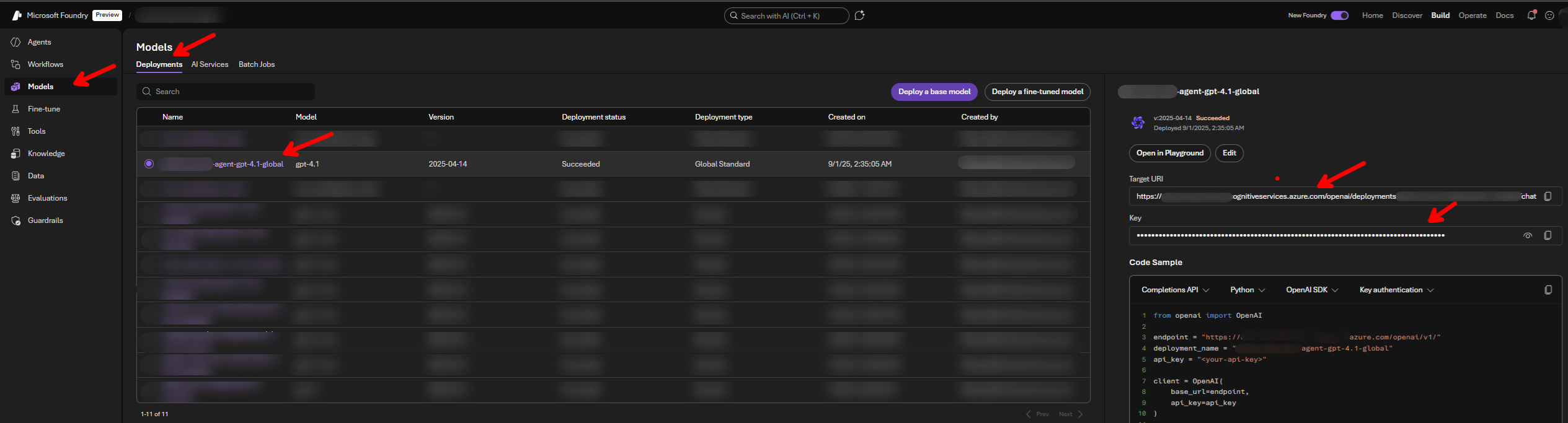

The documentations on the Langchain site and also on the Microsoft site seems to be outdated with the introduction of the Azure Foundry (new) interface.

So for setting up a Langchain model the URLs are a bit different.

The process for configuring LangChain to work with Azure’s AI models has recently changed due to the introduction of the new Azure Foundry interface. If you’ve found that the documentation on the LangChain site or older Microsoft documentation is leading to errors, the core issue is likely an outdated endpoint URL structure.

🔗 Identifying the Correct Azure Endpoint

The key change is in the required format for the model endpoint.

| Status |

URL Type |

Old/New Format |

Example Structure |

| ❌ Outdated |

LangChain Docs |

Old |

https://{your-resource-name}.services.ai.azure.com/openai/v1 or https://{your-resource-name}.services.ai.azure.com/models |

| ❌ Incorrect |

Found in Azure Foundry (New) API call |

Incorrect for LangChain |

https://{your-resource-name}.cognitiveservices.azure.com/openai/deployments/{your-deployment-name}/chat/completions?api-version=2024-05-01-preview |

| ✅ Correct |

Required for LangChain |

New |

"https://{your-resource-name}.cognitiveservices.azure.com/openai/deployments/{your-deployment-name}/" |

The correct endpoint for use with the langchain-azure-ai package must end after the deployment name

💻 LangChain Python Usage Example

The following code demonstrates how to correctly set up the necessary environment variables and initialize an agent using the AzureAIChatCompletionsModel class with the new endpoint format.

Prerequisites

You will need the langchain and langchain-azure-ai libraries installed.

pip install langchain langchain-azure-ai

Python Code

from langchain_azure_ai.chat_models import AzureAIChatCompletionsModel

from langchain.agents import create_agent

import os

os.environ["AZURE_AI_CREDENTIAL"] = (

"THE KEY THAT AZURE FOUNDRY AI GIVES"

)

os.environ["AZURE_AI_ENDPOINT"] = (

"https://<<PROJECT NAME>>.cognitiveservices.azure.com/openai/deployments/<<DEPLOYMENT NAME>>/"

)

os.environ["DEPLOYMENT_NAME"] = (

"<<DEPLOYMENT NAME YOU GIVE TO THE MODEL>>"

)

def get_weather(city: str) -> str:

"""Get weather for a given city."""

return f"It's always sunny in {city}!"

llm = AzureAIChatCompletionsModel(

endpoint=os.environ["AZURE_AI_ENDPOINT"],

credential=os.environ["AZURE_AI_CREDENTIAL"],

model=os.environ["DEPLOYMENT_NAME"],

)

agent = create_agent(

model=llm,

tools=[get_weather],

system_prompt="You are a helpful assistant",

)

# Run the agent

result = agent.invoke(

{"messages": [{"role": "user", "content": "what is the weather in sf"}]}

)

print(result)

Sources

07 Oct 2025

Sometimes requests are denied due to many reasons (like 429 Too Many Request) and it is wise to just retry. The retry can be set on multiple levels, in code (with polly), in service level or in api gateway with a simple policy. In this post I will focus on setting the retry on the Azure Api Gateway.

The following policy retries backend calls up to three times if they fail with certain status codes, waiting 10 seconds between attempts.

<backend>

<retry condition="@(context.Response != null && new List<int>() { 403, 404, 500 }.Contains(context.Response.StatusCode))" count="3" interval="10">

<forward-request buffer-request-body="true" />

</retry>

</backend>

Breakdown:

- The

retry block sets the conditions on witch it retries and also how many times and the interval

- the

forward-request is the important part with the buffer-request-body set to true, as this ensures that when we retry the request, the same body will be sent again. (This was a head-scratcher until we figured it out that is needed)

Adding logging to the retry

To better understand when and why retries happen, you can log each attempt using trace and custom variables. Here’s a more complete example that tracks retry counts and logs the retried operation.

<policies>

<inbound>

<base />

<set-variable name="someVariableFromRequest" value="@(context.Variables.GetValueOrDefault<JObject>("requestBody")?["someVariableFromRequest"]?.ToString())" />

<set-variable name="retryCount" value="0" />

...

</inbound>

<backend>

<retry condition="@(context.Response != null && new List<int>() { 403, 404, 500 }.Contains(context.Response.StatusCode))" count="3" interval="10">

<choose>

<when condition="@(context.Response != null && new [] { 403, 404, 500 }.Contains(context.Response.StatusCode))">

<set-variable name="retryCount" value="@((Convert.ToInt32(context.Variables.GetValueOrDefault<string>("retryCount", "0")) + 1).ToString())" />

<trace source="RetryPolicy" severity="information">@( "Retrying {Operation Name} request with parameter " + context.Variables.GetValueOrDefault<string>("someVariableFromRequest") + ". Attempt " + context.Variables.GetValueOrDefault<string>("retryCount") )

</trace>

</when>

</choose>

<forward-request buffer-request-body="true" />

</retry>

</backend>

...

</policies>

This approach makes it easier to see retry attempts in APIM’s trace logs, including which operation retried and what parameter values were used.

Sources

23 Sep 2025

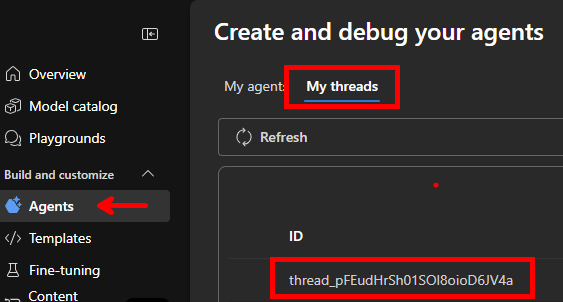

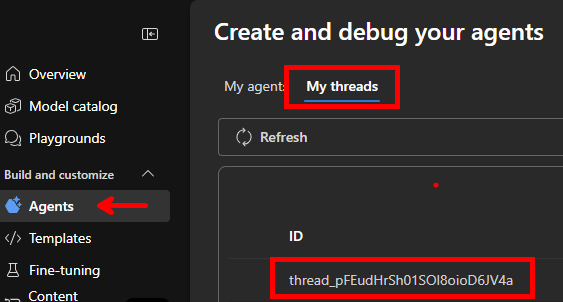

When building an agent with Azure AI Foundry, you’ll often need to look back at the conversation so far. Whether you’re debugging, showing it for reference, or implementing agent “memory” fetching thread message history is essential.

Install dependencies

You’ll need these packages:

- azure-ai-projects

- azure-ai-agents

- azure-identity

Install them with pip:

pip install azure-ai-projects azure-ai-agents azure-identity

Initialize the client

from azure.ai.projects.aio import AIProjectClient

from azure.identity.aio import DefaultAzureCredential

client = AIProjectClient(

endpoint="Endpoint of your Azure Ai Foundry project",

credential=DefaultAzureCredential()

)

Get thread ID

To fetch history, you need a thread ID. You can either persist it when creating threads in code or find it in the Azure AI Foundry portal:

List all messages in a thread

The simplest way is to iterate over all messages with the async list method:

agents_client = client.agents

msgs = agents_client.messages.list(thread_id=thread_id)

async for msg in msgs:

...

Limiting Results (API Calls)

The limit parameter is confusing. It does not cap the total number of messages returned—it only controls how many items are retrieved per API call. For example, limit=3 still fetches the entire history, just in smaller batches.

To truly process a limited number of messages, use paging and break early:

messages = agents_client.messages.list(thread_id=thread_id, limit=3)

for i, page in enumerate(messages.by_page()):

print(f"Items on page {i}")

for message in page:

print(message.id)

# break after first page if only X items are needed

this will produce something like this:

Items on page 0

msg_1

msg_2

msg_3

Items on page 1

msg_4

msg_5

msg_6

Items on page 2

msg_7

If you only want the first N messages, you can exit the loop after processing the desired count.

Sources